Highlights §

- I’ve been applying typical unit testing practices to machine learning code and it hasn’t been straightforward. In software, units are small, isolated pieces of logic that we can test independently and quickly. In machine learning, models are blobs of logic learned from data, and machine learning code is the logic to learn and use these derived blobs of logic. This difference makes it necessary to rethink how we unit test machine learning code. (View Highlight)

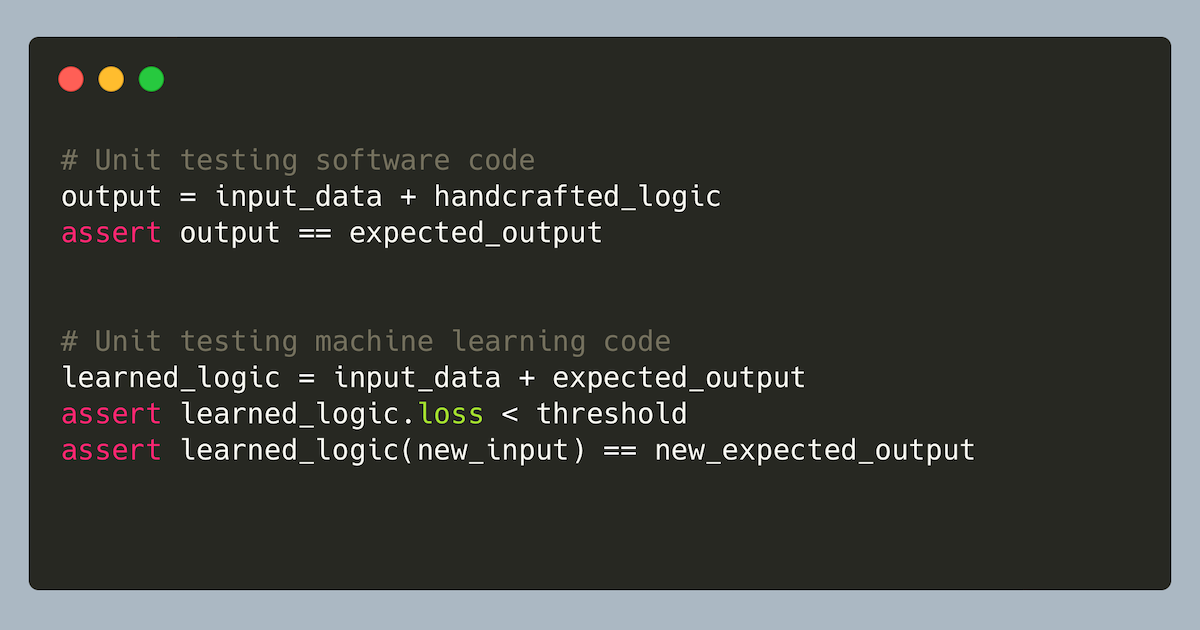

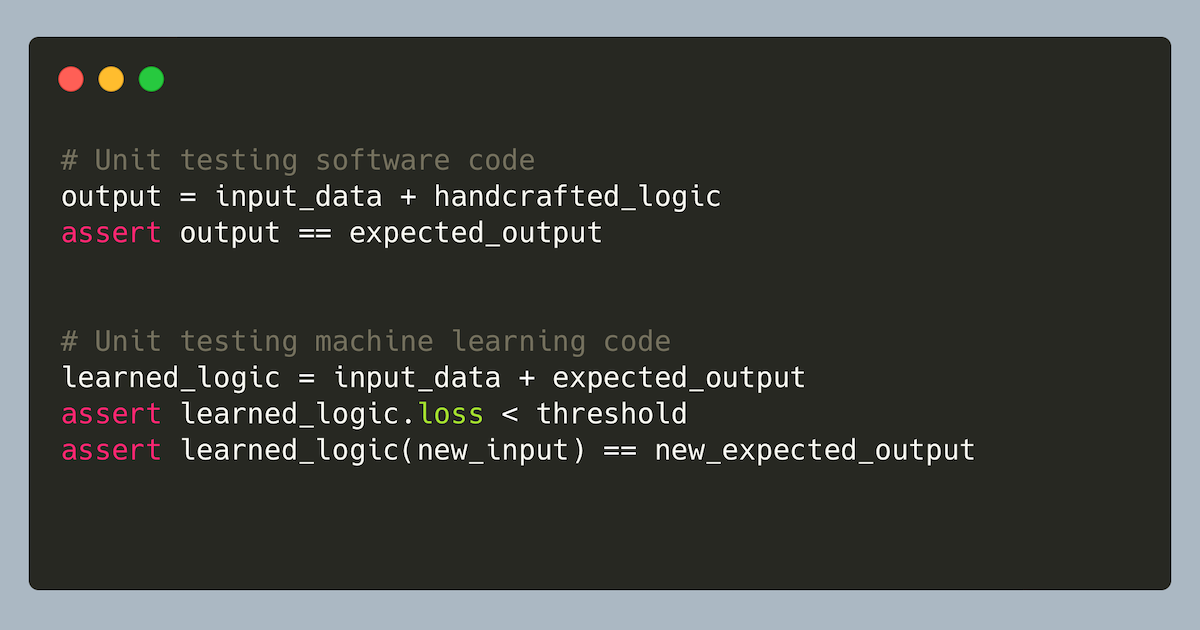

- In software, we write code that contains logic; in ML, we write code that learns logic and then uses that learned logic. Software code transforms input data + handcrafted logic into expected output. We can then test these outputs against asserts. In contrast, machine learning code transforms input data + expected output into learned logic (i.e., a model).

Software:Input Data+Handcrafted Logic=Expected Output (View Highlight)

- Machine Learning:Input Data+Expected Output=Learned Logic (View Highlight)

- Thus, in machine learning, instead of writing code that contains logic, we write code to learn logic, such as via building a decision tree or finetuning a hallucination classifier. Because the logic that acts on the input data is embedded within the model, if we want to test the learned logic, we’ll need to load the model, perform inference on some sample output, and then assert if the output matches the expected input. (View Highlight)

- In software, we typically mock dependencies like APIs; in ML, we want to test the actual model (sometimes). When unit testing software, it’s good practice to mock database calls, filesystem access, sending emails/push notifications, etc. In ML, there are scenarios where we’ll want to test against the actual model. (View Highlight)

- For example, we want to test that loss decreases with each batch and the model can overfit (before wasting compute on an hopeless run.) If the model is a classifier, we want to check that the inference logic is correct. For instance, two models may have different output classes: Google’s T5 NLI model classifies factual consistency with class = 1 while Meta’s BART NLI model classifies it with class = 2! (View Highlight)

- Use small, simple data samples. Avoid loading CSVs or Parquet files as sample data. (It’s fine for integration tests and evals but not unit tests.) Define sample data directly in unit test code—so that the test is self-contained—to test key functionality such as:

• Splitting into train/test tests when you have custom logic

• Custom implementations, such as Cosine or Euclidean distance in Java

• Preprocessing such as data augmentation or encoding

• Postprocessing such as diversification or filtering recommendations

• Error handling for empty or malformed input (View Highlight)

- When viable, test against random or empty weights. For example, we can initialize a model configuration with random weights to test output shape and device movement (from CPU to GPU and back). Here’s an example of how to initialize a model without having to download the weights and then assert the output shape (View Highlight)

- Write critical tests against the actual model. If they take a while to run, mark them as slow and run only when needed (e.g., pre-commit and pre-merge). Some essentials include:

• Verify training is done correctly, such as loss going down, model overfitting, and training till convergence on a small sample of data

• Verify model outputs match expectation, such as 0.99 = unsafe instead of safe

• Verify model server can start, take batch input, and return the expected output

Don’t test external libraries. We can assume that external libraries work. Thus, no need to test data loaders, tokenizers, optimizers, etc. (View Highlight)