Highlights §

- Before jumping into the solution, let’s talk about the problem. With RAG, we are performing a semantic search across many text documents — these could be tens of thousands up to tens of billions of documents.

To ensure fast search times at scale, we typically use vector search — that is, we transform our text into vectors, place them all into a vector space, and compare their proximity to a query vector using a similarity metric like cosine similarity. (View Highlight)

- For vector search to work, we need vectors. These vectors are essentially compressions of the “meaning” behind some text into (typically) 768 or 1536-dimensional vectors. There is some information loss because we’re compressing this information into a single vector. (View Highlight)

- Because of this information loss, we often see that the top three (for example) vector search documents will miss relevant information. Unfortunately, the retrieval may return relevant information below our top_k cutoff.

What do we do if relevant information at a lower position would help our LLM formulate a better response? The easiest approach is to increase the number of documents we’re returning (increase top_k) and pass them all to the LLM. (View Highlight)

- The metric we would measure here is recall — meaning “how many of the relevant documents are we retrieving”. Recall does not consider the total number of retrieved documents — so we can hack the metric and get perfect recall by returning everything. (View Highlight)

- Unfortunately, we cannot return everything. LLMs have limits on how much text we can pass to them — we call this limit the context window. Some LLMs have huge context windows, like Anthropic’s Claude, with a context window of 100K tokens [1]. With that, we could fit many tens of pages of text — so could we return many documents (not quite all) and “stuff” the context window to improve recall?

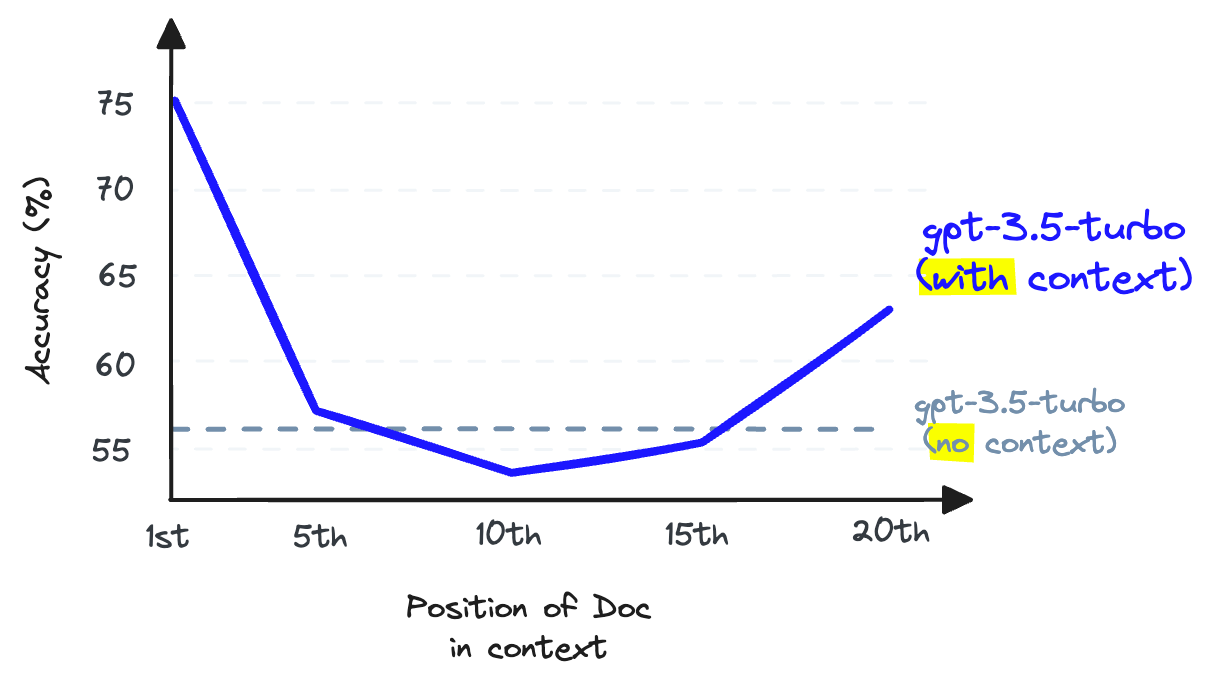

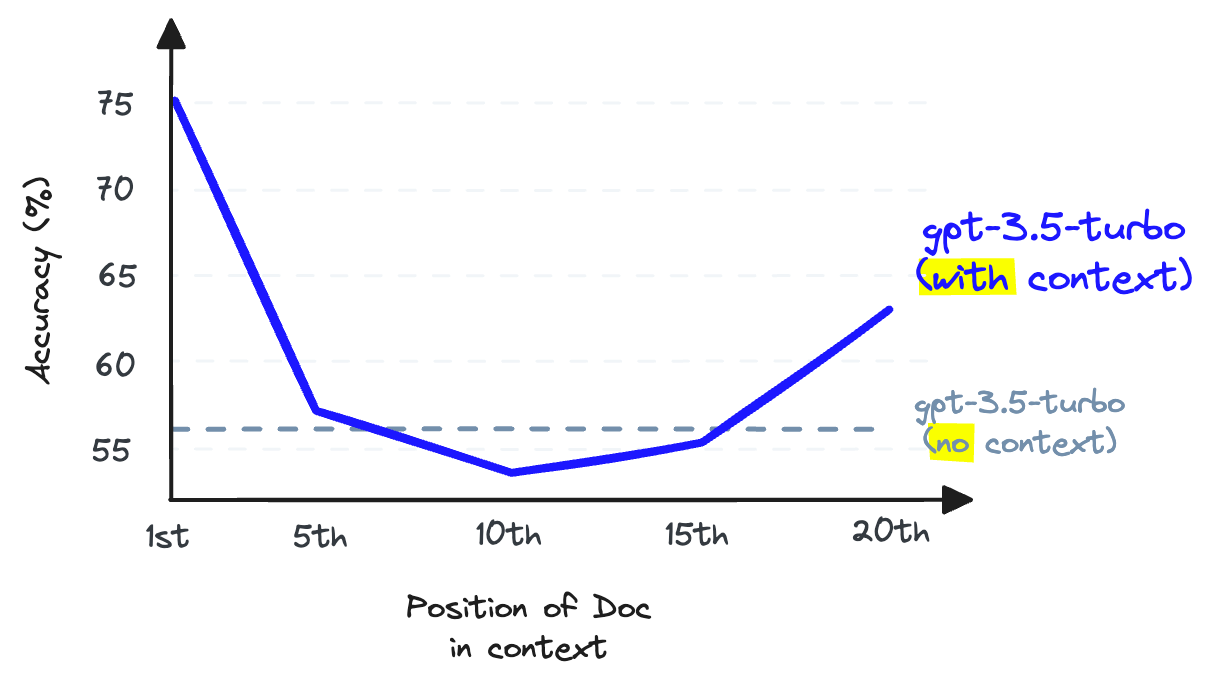

Again, no. We cannot use context stuffing because this reduces the LLM’s recall performance — note that this is the LLM recall, which is different from the retrieval recall we have been discussing so far.

When storing information in the middle of a context window, an LLM’s ability to recall that information becomes worse than had it not been provided in the first place [2]. (View Highlight)

When storing information in the middle of a context window, an LLM’s ability to recall that information becomes worse than had it not been provided in the first place [2]. (View Highlight)

- LLM recall refers to the ability of an LLM to find information from the text placed within its context window. Research shows that LLM recall degrades as we put more tokens in the context window [2]. LLMs are also less likely to follow instructions as we stuff the context window — so context stuffing is a bad idea.

We can increase the number of documents returned by our vector DB to increase retrieval recall, but we cannot pass these to our LLM without damaging LLM recall.

The solution to this issue is to maximize retrieval recall by retrieving plenty of documents and then maximize LLM recall by minimizing the number of documents that make it to the LLM. To do that, we reorder retrieved documents and keep just the most relevant for our LLM — to do that, we use reranking. (View Highlight)

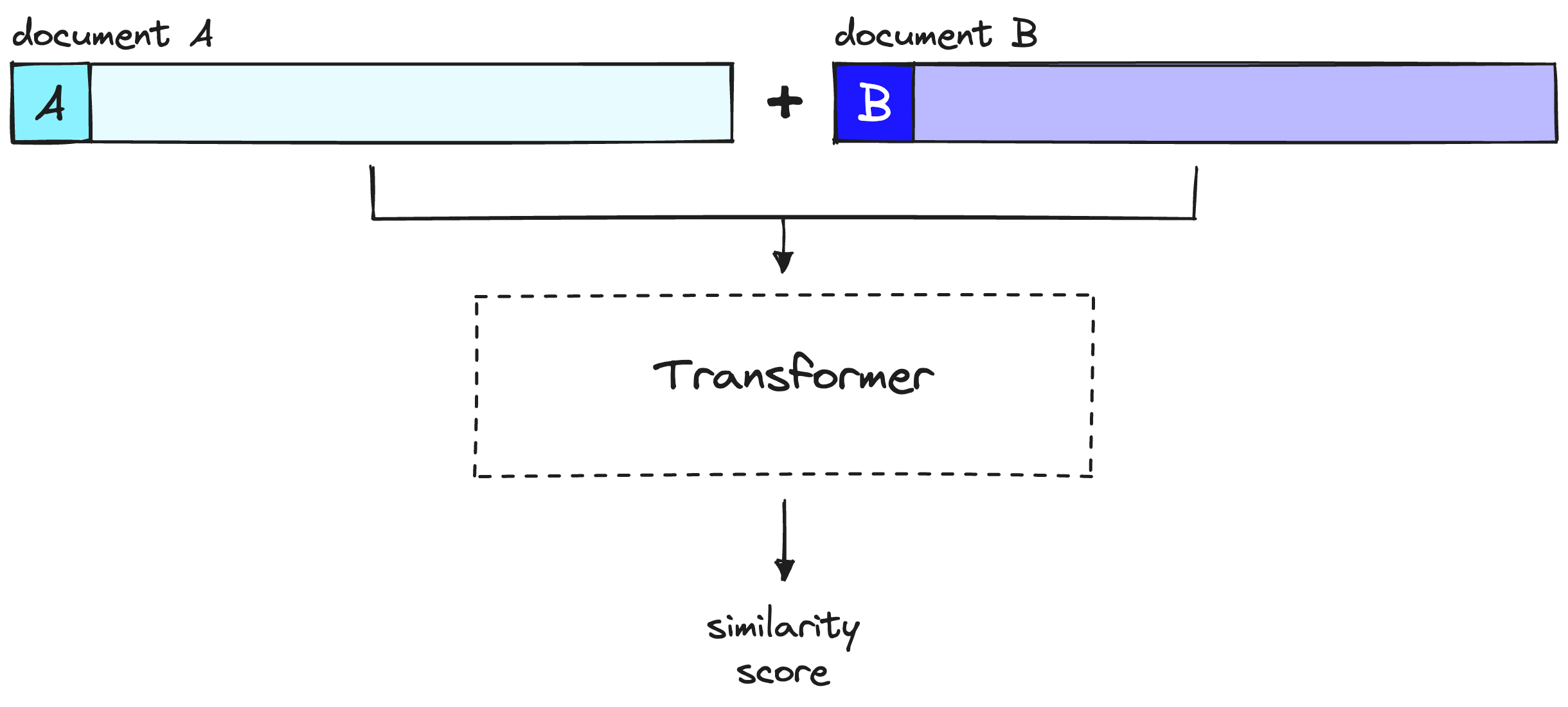

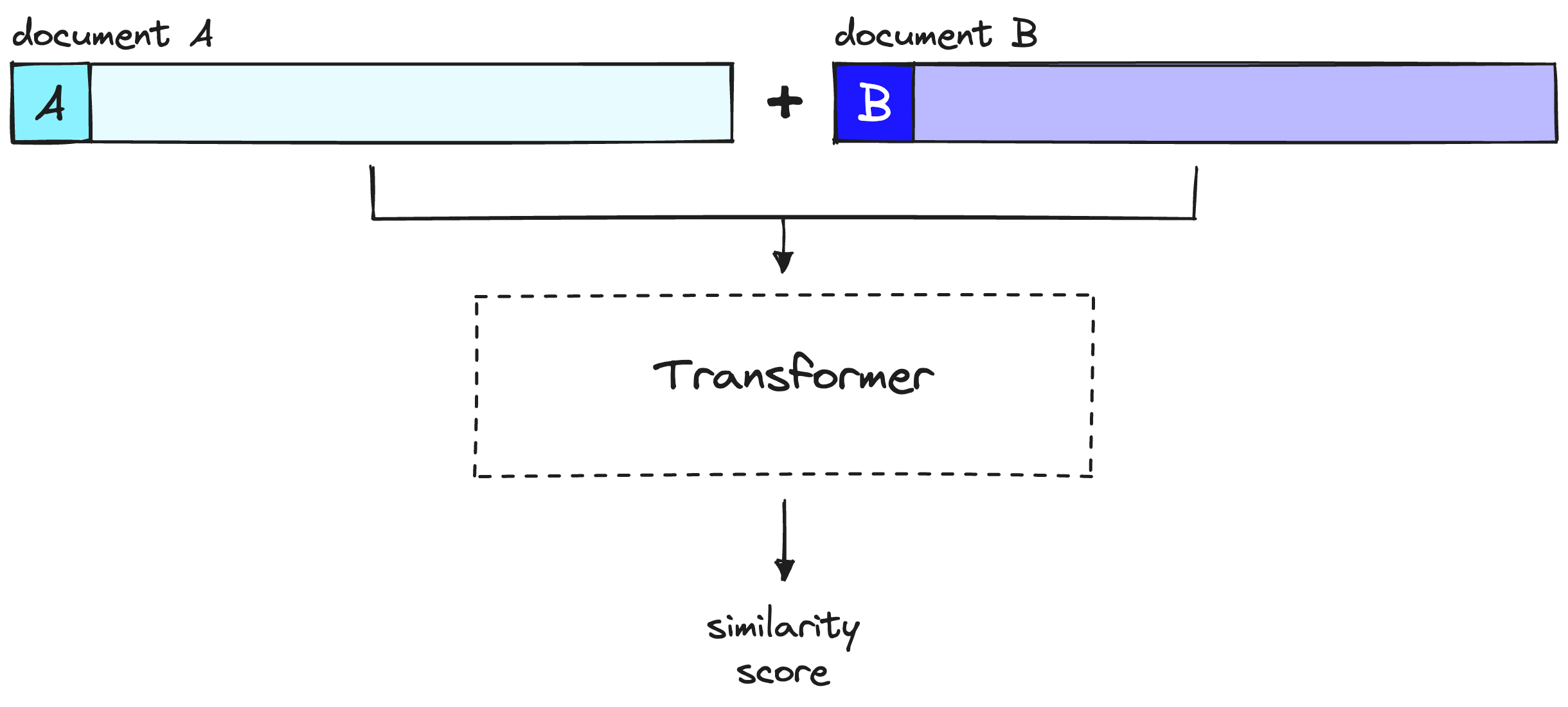

- A reranking model — also known as a cross-encoder — is a type of model that, given a query and document pair, will output a similarity score. We use this score to reorder the documents by relevance to our query. (View Highlight)

- Search engineers have used rerankers in two-stage retrieval systems for a long time. In these two-stage systems, a first-stage model (an embedding model/retriever) retrieves a set of relevant documents from a larger dataset. Then, a second-stage model (the reranker) is used to rerank those documents retrieved by the first-stage model.

We use two stages because retrieving a small set of documents from a large dataset is much faster than reranking a large set of documents — we’ll discuss why this is the case soon — but TL;DR, rerankers are slow, and retrievers are fast. (View Highlight)

- If a reranker is so much slower, why bother using them? The answer is that rerankers are much more accurate than embedding models.

The intuition behind a bi-encoder’s inferior accuracy is that bi-encoders must compress all of the possible meanings of a document into a single vector — meaning we lose information. Additionally, bi-encoders have no context on the query because we don’t know the query until we receive it (we create embeddings before user query time).

On the other hand, a reranker can receive the raw information directly into the large transformer computation, meaning less information loss. Because we are running the reranker at user query time, we have the added benefit of analyzing our document’s meaning specific to the user query — rather than trying to produce a generic, averaged meaning.

Rerankers avoid the information loss of bi-encoders — but they come with a different penalty — time. (View Highlight)

- When using bi-encoder models with vector search, we frontload all of the heavy transformer computation to when we are creating the initial vectors — that means that when a user queries our system, we have already created the vectors, so all we need to do is:

- Run a single transformer computation to create the query vector.

- Compare the query vector to document vectors with cosine similarity (or another lightweight metric). (View Highlight)

- With rerankers, we are not pre-computing anything. Instead, we’re feeding our query and a single other document into the transformer, running a whole transformer inference step, and outputting a single similarity score.

(View Highlight)

(View Highlight)

- Reranking is one of the simplest methods for dramatically improving recall performance in Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) or any other retrieval-based pipeline.

We’ve explored why rerankers can provide so much better performance than their embedding model counterparts — and how a two-stage retrieval system allows us to get the best of both, enabling search at scale while maintaining quality performance. (View Highlight)

When storing information in the middle of a context window, an LLM’s ability to recall that information becomes worse than had it not been provided in the first place [2]. (View Highlight)

When storing information in the middle of a context window, an LLM’s ability to recall that information becomes worse than had it not been provided in the first place [2]. (View Highlight) (View Highlight)

(View Highlight)